At the end of April, you'll start seeing memes of Justin Timberlake everywhere with the text "it's gonna be may." This, of course, is a reference to the 2000 hit song "It's Gonna Be Me," where Justin sings the hook. Only except of the expect "me," he sings "may." The meme itself dates back to 2012, but it has proven enduring as a cyclical meme. It reminds of us of both the hopeful month of May and how weird it was that pop stars used to sing like that. If you need a reminder or you've never heard the song before, here's a clip of the offending pronunciation:

- "Baby, when you finally get to love somebody, guess what: it's gonna be may." - It's Gonna Be Me, N'Sync (2000)

Justin is not the only pop star to sing "me" as "may." We've all probably heard a pop star sing something like "I'm missing you like canday" or "I want to be the minoritay." The nameless but frequent phenomenon even inspired an Atlas Obscura investigation by Dan Nosowitz.

But tracing the pedigree of this feature has eluded most of the people who write about it. Nosowitz's article offers an explanation for why it happens now, but it doesn't tell us who first started using it. Moreover, it confuses the vowel in "it's gonna be may" with a different vowel entirely, which muddies the waters even further. He refers to Stevie Wonder saying "thirteen month old babay," but that's not actually what Stevie Wonder is saying: he's saying "thirteen month old bab-IH," with a short 'i' and no diphthong. These two vowels have separate histories and need separate accounts.

- "Thirteen month old babee [beɪbi] ... thirteen month old babih [beɪbɪ]." - Superstition, Stevie Wonder

So why does it matter which vowel happened - singers change their vowels all the time, right? Well, most linguistic changes of this sort aren't random or arbitrary - there is usually a reason that sound changes happen, and a reason that they spread as well. The spread of "may" and "babay" doesn't seem to be caused by random innovation - it's a daisy chain of influence from disparate genres and peoples all reaching their zenith in the massive pop moment of the 90s.

I first tackled this subject in 2016 (re-published in 2017) in one of my earliest articles. This is not just a rewrite, but a totally new theory to explain just why pop singers do that thang. I hope you'll join me in what is probably the most comprehensive history of "it's gonna be may" yet.

Setting the boundaries

First, let's talk about "it's gonna be may." What’s happening is the "ee" [i] vowel is being converted to "ay" [ɪi]. This is an example of diphthongization, or a vowel "breaking" into two vowels. This breaking can apply to other words that have an 'ee' /i/ sound in them, like "knees" /niz/ can become "knays" [nɪiz]. We’ll call this pattern ‘ME-breaking.’ There some dialects that have ME-breaking commonly, like Southern American English (Lee, 2012; McDorman) and London English.

- "He loves mee [mi]." No breaking.

- "He loves may [mɪi]." Breaking.

Words like ‘happy’ and ‘sadly’ have an ‘ee’ sound in them, but the stress doesn’t fall on the ‘ee.’ This puts them in a separate category, called ‘HAPPY’ words. Nowadays, most dialects of English have an ‘ee’ sound in these words: this is called tense-HAPPY.

But in the 1800s, these HAPPY words were pronounced with a short 'i' [ɪ] sound. So they sounded like ‘happih’, ‘verih’, ‘anarchih.’ This pronunciation is called 'lax-HAPPY'. While lax-HAPPY isn’t popular nowadays, older speakers of conservative Received Pronunciation (Wells, 1980), Southern American English (Thomas, 2006), and African American English still use it.

So what if you had breaking in a HAPPY word? This would result in ‘happay.’ There’s no agreed-upon term for this, but I’ll call it HAPPY-breaking. You can find HAPPY-breaking in working class varieties of London English and in Yorkshire varieties, among others.

- "She is happee [hæpi]." Tense-HAPPY

- "She is happih [hæpɪ]." Lax-HAPPY

- "She is happay [hæpɪi]." HAPPY-breaking

To keep things simple, I will use the IPA symbols [ɪi] to note that a word has vowel breaking: m[ɪi]. This is because the vowel breaking in "it's gonna be may" isn't actually identical to the sound in the word "May." Some instances of vowel breaking are not as obvious and will not sound as close to the word "May." I am less interested in the degree of breaking and more interested in the fact that it occurs at all, so both subtle and obvious breaking will be written with [ɪi].

Timeline

Here's the fun part: we're going to look at popular songs from the 20th century to find out who started this whole ME-breaking and HAPPY-breaking mess. To keep things simple, I mostly focused on songs that topped on the Billboard Hot 100, which is an American popular music chart. An even more comprehensive review would compare this with the UK charts or also look at songs that charted below #1, but I am just one person and listening to every #1 hit of the 80s was enough work for me.

One question we're going to try to tackle here is how could singers have been exposed to "may" and "babay"-like forms? Remember, it's unlikely that multiple people over multiple decades just happened to come up with vowel-breaking on their own, so we have to posit an explanation for how they picked up on it.

Unfortunately, there are rarely direct examples of a singer saying "I sang it like this because I heard it from this person/someone told me to." As such, we have to rely on some circumstantial evidence at times - such is the nature of tracing influences in pop music history. Sometimes we're lucky and we know that a singer was a fan of early singers because they've done covers of their material. Sometimes they even do interviews. Sometimes we have to rely on genre similarities and the fact that musicians tend to be aware of other people working in their scene. But sometimes there's no obvious explanation. Tracing history is rarely clean.

1950s-1960s: Lonesome Cowboy

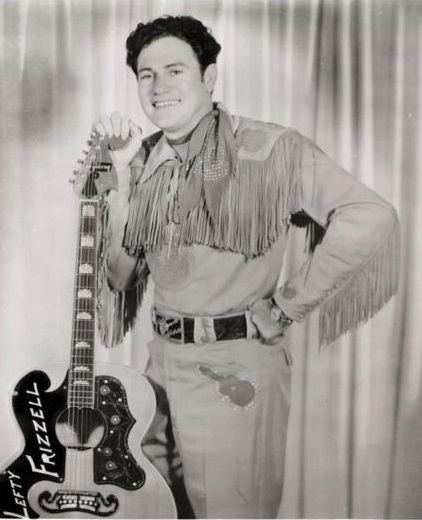

The earliest example of ME-breaking I've been able to find so far is in country music, by Southern American English speakers. Lefty Frizzell had a hit in the 1951 song "Give me more, more, more (of your kisses)," and also some ME-breaking. Another example is in his unreleased 1951 song, "You Want Everything But Me."

- "They'll even pay the weddin' bills to just get rid of m[ɪi]" - Give Me More, More, More (Of Your Kisses), Lefty Frizzell (1951)

- "You want everything but m[ɪi]" - You Want Everything But Me, Lefty Frizzell (recorded in 1951s, released 1981)

Another Southern country singer was Waylon Jennings. He sang a cover called "She Called Me Baby" in 1967 with some HAPPY-breaking.

- "She called me baby, bab[ɪi]" - She Called Me Baby, Waylon Jennings (1967)

You could also find some breaking in jazz. The singer Chris O'Connor was Missouri born and raised, and has a diphthongized 'me' in S'Wonderful.

- "That you should care for m[ɪi]" - S'Wonderful, Chris O'Connor (1957)

Overall, breaking in popular music is limited to Southerners in these two decades.

To my surprise, I was unable to find examples of African American singers with ME-breaking. ME-breaking appears to be more a characteristic of Southern American English than African American English, including Southern African American English. I haven't found examples of ME-breaking in the literature for African American English. I listened to influential black blues and rock 'n' roll artists such as Muddy Waters, Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, and Little Richard, and Fats Domino, but they had no ME-breaking at all! (There was some lax-HAPPY, but remember that that is a different feature. Don't worry, I'm covering it in another article in the future.)

1970s-1980s: the Rock and Punk Years

The earliest example of breaking in rock music is the Rolling Stones. This group also happens to be from London, which is a region with ME-breaking. You can hear an example of it in their song "It's Only Rock and Roll (But I Like It)," from 1974:

- "I said can't you say s[ɪi]" - It's Only Rock and Roll (but I Like It), the Rolling Stones (1974)

In 1975, an American-English rock group called the Arrows recorded a response to this song, called "I Love Rock and Roll." Their American lead singer also gave ME-breaking a try:

- "I saw her dancin' there by the record mach[ɪi]ne ... And I could tell it wouldn’t be long till she was with m[ɪi], yeah, m[ɪi]." - I Love Rock 'n' Roll, The Arrows (1975)

Then in 1976, the English punk group the Sex Pistols released their first single “Anarchy in the UK.” Besides being massively successful, it also had ME-breaking (be -> bay) and pronounced HAPPY-breaking (anarchy > anarchay).

- "I want to b[ɪi] anarch[ɪi]" - Anarchy in the U.K., the Sex Pistols (1976)

The singer Johnny Rotten came from a working-class household in London, so this ME-breaking wasn’t copped from country music. You can hear in this interview how he makes 'week' sound more like 'wake':

(1:07) Watch Top of the Pops and send their boring little letters into Melody Maker w[ɪi]k after w[ɪi]k.

From here, both ME-breaking and HAPPY-breaking appear sporadically throughout the 80s. The 1982 cover of I Love rock and roll by Joan Jett is the first #1 US hit of the 80s to feature ME-breaking, imitating the same vowel that the arrows used.

- "He was looking at me, yeah, m[ɪi] ...take your time and dance with m[ɪi]" - I Love Rock 'n' Roll, Joan Jett & the Blackhearts (1982)

1986 had the top 10 hit by the Beastie Boys, “You gotta fight for your right to party.” Although the Beastie Boys were basically a rap group by that time, they started out as a hardcore punk band and the influences can still be heard in their instrumentation. Perhaps there’s also some influence in their vowels, because we hear HAPPY breaking:

- "You gotta fight for your right to part[ɪi]!" - (You Gotta) Fight For Your Right (To Party), the Beastie Boys (1986)

ME-breaking hadn't just infiltrated classic rock and punk - it also made its way into glam rock. The 1987 song, "Pour Some Sugar On Me" by the English group Def Leppard should perhaps be called "Pour Some Sugar On May."

- "Pour some sugar on m[ɪi]"- Pour Some Sugar On Me, Def Leppard (1987)

The 1990s and beyond: Pop Takes Over

As we leave the 80s, we can tell one thing. ME-breaking and HAPPY-breaking had firmly entrenched themselves in rock and rock-adjacent genres. You'll find examples of ME-breaking and HAPPY-breaking in rock music throughout the 90s. One could even consider them to be a part of what it means to sing rock music: a part of a rock singer "register." My favorite 90s-era of ME-breaking and subtle HAPPY-breaking is the theme song to the video game Sonic Adventure, which is a beautiful example of all the cliches associated with rock music at the end of the decade.

- (upper harmony) I don't know what it can be but you drive me craz[ɪi] ... open your heart and you will s[ɪi]" - Open Your Heart, Crush 40 (1998)

However, knowing the path it took for ME-breaking and HAPPY-breaking to get into rock music doesn't explain how it got into pop music. That path is a little more mysterious and murky - but we're going to tread it anyway.

In 1994, rapper Notorious B.I.G. posthumously released "Juicy." The Brooklyn girl group Total sings on the hook:

- "You had a goal but not that man[ɪi]" - "Juicy", The Notorious B.I.G. (ft. Total) (1994)

The chorus was interpolated from Mtume's song "Juicy Fruit" 1983, but this original version did not have HAPPY-breaking. Why did this girl group use HAPPY-breaking on the pop hook of a rap song? Perhaps influence from growing up around rock music? It's not clear, but what is clear is that this song was a massive hit, spreading HAPPY-breaking across the airwaves.

HAPPY-breaking and ME-breaking both appear in an unusual place in the 90s - Mariah Carey’s #1 hit song “Always Be My Baby.” This is one of the earlier places in pure pop music where we see HAPPY-breaking and exaggerated ME-breaking.

- "Boy, don't you know you can’t escape m[ɪi]? Ooh darlin' cuz you’ll always be my bab[ɪi]" - Always Be My Baby, Mariah Carey (1995)

Like with "Juicy," it's not clear how Mariah came across this form. Perhaps she picked it up from "Juicy" - Mariah was a noted fan of hip-hop. She was also a noted fan of glam rock - she's covered songs by Def Leppard, which we noted were big users of this sort of breaking.

HAPPY-breaking makes a re-occurrence in the song “Quit playing games with my heart” by the Backstreet Boys. This song was produced by the Swedish producer Max Martin, a fact that we'll revisit later.

- "Bab[ɪi], so bad, bab[ɪi], quit playing games with my heart." - Quit Playing Games (With My Heart), the Backstreet Boys (1994)

Then we have "Wannabe", released in 1996, has subtle ME-breaking by Mel B. Mel is from West Yorkshire, another region with ME-breaking. (Source).

- "And as for m[ɪi]? Ha, you’ll see!" - Wannabe, Spice Girls (1996)

In 1999, HAPPY-breaking and ME-breaking reached levels of vowel-breaking heretofore only dreamed of by man with Mandy Moore talking it all the way. This is one of the most obvious and exaggerated uses of HAPPY-breaking. It shows that by this point, HAPPY-breaking and ME-breaking had become associated with contemporary pop music.

- "This feelin’s got me week in the kn[ɪi]s... come to m[ɪi], sw[ɪi]t to m[ɪi]... I'm missing you like cand[ɪi]" - Candy, Mandy Moore (1999)

It all comes full circle in the year 2000. N'Sync released “It’s gonna be me,” which topped the US charts for two weeks. The song has both normal 'me' and ME-breaking, which makes them easy to compare. No HAPPY-breaking, though.

- "I remember you told m[ɪi] ...It’s gonna be m[ɪi] ... but in the end you know it's gonna be m[i]. It's gonna be m[ɪi], it's gonna be m[ɪi], gonna be m[ɪi]"

Justin was asked about this pronunciation in an interview and said something rather interesting:

Justin: I will say in my defense Max Martin made me sing 'me' that way. [...] I just want to throw Max Martin on the chopping block for that one.

[...] Anchor: Did he give a reason for that?

Justin: I think he just wanted me to sound like I was from Tennessee. [...] He just kinda likes that.

Max Martin gave him direction on how to sing. Max Martin, if you'll remember, also produced "Quit Playing Games With My Heart," which had HAPPY-breaking. Perhaps he also guided the Backstreet Boys in using this pronunciation.

Timberlake clearly associated it with southerners as opposed to english punk rockers, but Max Martin was a fan of hard rock, so it’s likelier that Max Martin heard the pronunciation from them and decided to use it. He also could have picked up on it from Mariah Carey and the Spice Girls - he listened to pop music and could tell a trend when he heard one.

Noticeably, a number of Max Martin produced songs feature ME-breaking. This may seem coincidental, but Max Martin has been known to record demos of songs before giving them to singers, and telling them to copy the performance as much as they can. Another popular singer he worked with was, of course, Britney Spears. (She has enough linguistic peculiarities otherwise to merit her own article.)

- There's nothing you can do or say, bab[ɪi] ... I'm not your property as from today, bab[ɪi]

Martin is known to be controlling about the music he writes. Music journalist John Seabrook writes:

And yet Martin is known to insist that the artists he works with sing his songs exactly the way he sings them on the demos. In a sense, Spears, Perry, and Swift are all singing covers of Max Martin recordings. They are also among the few people in the world who have actually heard the originals. Countless self-proclaimed performers on YouTube sing Max Martin songs, but there is not a single publicly available video or audio recording of Martin performing his own stuff. (In the course of researching my book “The Song Machine,” I got to hear an actual Max Martin demo, for “… Baby One More Time,” when a record man who had it on his phone played it for me. The Swede sounded exactly like Spears.)

If true, this would go a long way to explaining why other artists who have worked with Martin use breaking. For example, Martin worked on Katy Perry's song "Part Of Me." In this demo, she even rhymes "me" with "way" twice:

- "I just wanna throw my phone away, find out who is really there for m[ɪi]... You can take the dog from m[ɪi], I never liked him anyway. In fact you can take everything except for m[ɪi]."

2010-era pop songs don't have to be produced by Max Martin, but his imprint is still strong. Taylor Swift's song "Out of the Woods" was produced by Jack Antonoff, but she still uses ME-breaking on the high notes.

- "You were looking at may [mɪi], you were looking at may [mɪi], you were looking at may [mɪi]."

The Run-down

So we've traced the path that HAPPY-breaking and ME-breaking have taken through pop history. HAPPY-breaking and ME-breaking are no longer hot and trendy. But they haven't faded away entirely - instead, they've found a home in the linguistic toolbox of singers. They've expanded from the rock singer register to the pop singer register. Perhaps this is why we don't even comment on contemporary singers who still use it; it's become invisible to us as a sign of pop-ness.

The question to ask is why singers found these features so appealing. There are plenty of other vowels they could have used, after all. Why these?

Bio-mechanics and song

Nosowitz's Atlas Obscura article has an important point: close vowels, like 'ee' [i], are harder for singers to sing with than more open vowels like 'ih' [ɪ]. If you'll look back at a lot of the examples, you'll notice that breaking is more common on sustained or high notes. I personally do find it easier to sing high/sustained notes on 'ih' and 'ey' than on 'ee' (Mitrano, 2002).

Changing vowels to make singing easier or more 'beautiful' isn't unusual at all in sung speech. Classical singers have to learn the correct vowel placements to get the large, resonant and particular sound they need (Nix, 2004). These vowel placements are not the same as you would find in spoken speech! Pop singers are not usually classically trained, but you don't need classical training to experience the bio-mechanical feedback when you sing 'ee' on a high note versus 'ey.'

What if you could used these sounds on a lower note, which doesn't need the help of a different vowel? Vocal coach Lis Lewis (quoted in Atlas Obscura) suggests that "this is an attempt to co-opt the signifiers of intensity without actually needing to use them." This would match with JC Chasez's recollection of how "It's Gonna Be Me" was recorded:

[...]But because "It's Gonna Be Me" has become a meme for the month of May, it was interesting when we cut that record. It was actually a very conscious choice to say it that way, because we wanted it to really punch.

For certain words, we bent the pronunciation. We were hitting the L's hard on "lose." Instead of saying, "You don't wanna lose" -- which would be kind of boring -- we'd be like "You don't wanna NLUUSE." But when you're listening to someone in the studio singing it that way, at first you're like, "What is wrong with you?" But you have to dig and hit these different shapes of consonants and vowels to give them energy. Instead of saying, "It's gonna be ME" we said "ET'S GONNA BAY MAY!" for it to hit harder.

Those conscious choices sound funny from the outside, but when it all comes together it sounds amazing. There weren't memes back then, but we knew it needed to be more.

There is another process we need to consider before coming to the conclusion that it's all "fake energy"...

The process of enregisterment

A register is "a particular socially identifiable variety of a language." The classic examples are of formal and informal registers: a person who is giving a public speech will be speaking in a more formal register than someone who is hanging out at home with their friends.

You can also broaden the concept to refer to things like how English speakers can put on a 'vampire voice' by saying "I vant to suck your blod." Internet linguist Gretchen McCulloch points out that this is because one of the most iconic Draculas was played by Bela Lugosi, a Hungarian man with a Hungarian accent. So when Adam Sandler's vampire character in "Hotel Transylvania" says "welcome to hot'el trenseelvenia," he's not trying to communicate that his character is Hungarian - he's trying to communicate that he's a vampire. We call this association of linguistic features with an identity "enregisterment."

This concept can also apply to music. Originally, the people who said "may" and "happay" were just using their own Southern or London accents. But when singers started copying their pronunciation, they removed breaking from its origins. In turn, these features were re-analyzed and "enregistered" as part of a rock register. As the feature kept popping up in smash songs, it also became enregistered in the pop register.

Registers aren't mandatory - you can have vampires without Eastern European accents. But registers do communicate something: your awareness of belonging to that group. A rock or pop singer who uses "may" is able to signal their awareness of rock and pop singing styles (not to mention make use of a useful vowel modification in difficult songs).

That doesn't make using "may" a sign of fakeness or inauthenticity. Registers aren't always explicitly taught or acquired. You can learn different registers by osmosis: Just being in a different linguistic environment makes people change their own speech to sound more like everyone else. This is called "accommodation" and it's a sign of good faith and wanting to make things easier for other people (West & Lynn, 2017, p. 468-469).

Conclusion

Linguistic innovations happen all the time, but not all of them catch on. With HAPPY-breaking and ME-breaking in music, we are lucky to have such a long corpus of recorded music to use to trace its origins. The spread of breaking is a fascinating example of how different genres of music interact with and define each other. It's also an example of how modality-specific features can make a difference: it helps that breaking made it easier to sing harder notes.

Despite the massive spread of breaking in music, it remains locked to sung speech. Nobody starts saying "I hope you love may" or "I hope you're happay" in speech unless they're joking (or speak one of the varieties of English that we mentioned with these features). This also illustrates another feature: how we are clearly able to distinguish between registers. A singer can say "it's gonna be may" multiple times in a song and then get on an interview and use "me" consistently the entire time. Sung speech and spoken speech registers aren't anywhere as porous as the different genre registers are.

In the Atlas Obscura article, Nosowitz writes that it is surprising that nobody has taken the linguistics of pop music seriously considering how obvious the difference is, even for lay people. There is a treasure trove of interesting information for both linguists and musicologists in sung speech, if we only care to listen. After all, the simple meme that started this whole thing was almost 60 years in the making.

Works Cited

- Wells, John. 1980. Accents of English.

- Thomas, Erik R. 2006. Rural white Southern Accents.

- Lee, Campbell & Jacobs, Debra. 2013. Chapter 9: "The Linguistic Place of the Floridian Speaker of Standard African American English: Dimensions of Ethnicity, Region, and Style" in Florida Studies: Selected Papers from the 2012 and 2013 Annual Meetings of the Florida College English Association, edited by Paul D. Reich, Andrew Leib.

- Seabrook, John. 2015. "The Song Machine: Inside the Hit Factory."

- Seabrook, John. Blank Space: What Kind of Genius Is Max Martin?. The New Yorker.

- Nosowitz, Dan. 2016. Why Justin Timberlake Sings ‘May’ Instead of ‘Me’. Atlas Obscura.

- McCulloch, Gretchen. 2019. ‘Boomerspeak’ Is Now Available for Your Parodying Pleasure. Wired

- Sampson, John. 1997. « Genre », « Style » and « Register ». Sources of confusion ?. Revue belge de Philologie et d'Histoire.

- McCoy, Scott Jeffrey. 2004. Your voice, an inside view.

- Nix, John. 2004. Vowel Modification Revisited.

- West, Richard & Turner, Lynn. 2017. Introducing Communication Theory: Analysis and Application

- Mitrano, Melanie. 2002. The New Music Connoisseur. Vowels and Word Articulation. ("Closed vowels, as in the words greet and moon, are difficult to sing and articulate in the upper range.")

There is an accent somewhere in England where 18 comes out as [aitein].

ReplyDeleteSounds like traditional Cockney to me!

DeleteAnd I just realized that the interviewers in the Justin Timberlake interview have ME-breaking themselves (or more accurately FLEECE-breaking). This sort of diphthongization seems very common in southern English English nowadays.

Dear Karen, thanks for your blogs. I always stay up to date whenever a new post arrives. I wanted to share this video with you, as I thought it might give you some new thoughts on the specific topic addressed above.

ReplyDeletehttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y4J1vZAV4kY&list=PL5ag0TICVq2WkrHun4lLXvn2e-SgGLCDC&index=37&ab_channel=VoixtekSingingLessonswithRonAnderson